- Debates

Features

Topics

Upcoming debates

-

-

-

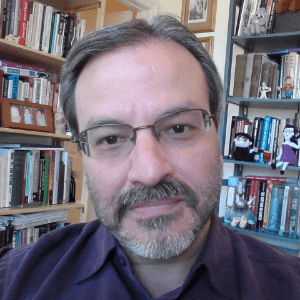

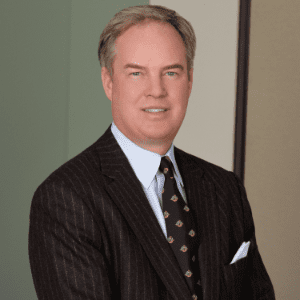

Happiness is a complex emotion and mental state, one that has been pondered since the times of the Ancient Greeks. Many have wondered what it means to be happy and to achieve happiness through either virtue or pleasure. Is it for the good of the individual or the benefit of society? Those who believe virtue is the key to happiness argue that it is important for the well-being of both the individual and society, as touted by the Founding Fathers and the Stoics and inspired by Jeffrey Rosen's book "The Pursuit of Happiness", as one should strive for a life of moral virtue and rationality. Those who believe pleasure is the key to happiness see it as the maximization of pleasure and the minimization of pain. Quoting philosophers such as Epicurus and John Stuart Mill and touting Roger Crisp's "Reason and the Good", they also argue that everyone should have the liberty to define their sources of happiness and seek them as they see fit. With this background in mind, we debate the question: The Pursuit of Happiness: Virtue or Pleasure?Friday, May 17, 2024

-

- Insights

- About

-

SUPPORT OPEN-MINDED DEBATE

Help us bring debate to communities and classrooms across the nation.

Donate

- Header Bottom

JOIN THE CONVERSATION